By William Schomberg and Andy Bruce

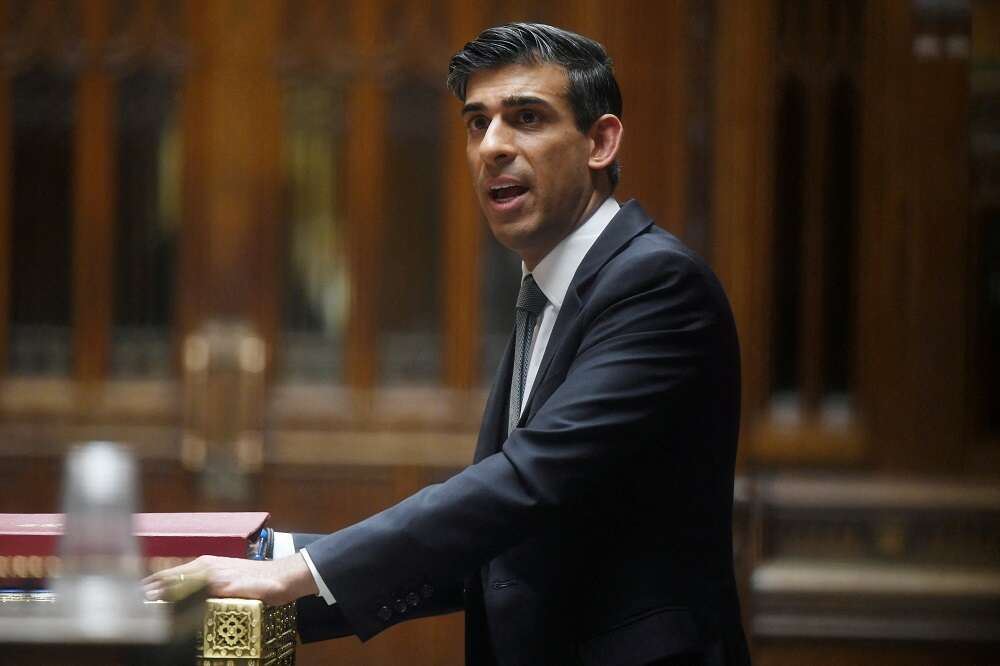

LONDON (Reuters) -British finance minister Rishi Sunak faced broad criticism on Thursday for not giving enough help to poorer households as the country heads for its biggest drop in living standards since at least the 1950s.

After earning plaudits for his response to the coronavirus crisis in 2020, Sunak was under fire for what fiscal analysts said looked like a plan to hold back money for giveaways to voters ahead of Britain’s next national election.

Sunak announced reductions in fuel duty and taxes on wages including an income tax cut in 2024 in a budget update on Wednesday, telling parliament it represented the biggest net cut to personal taxes in over 25 years.

But the measures were met with howls of protest, and not only from opposition lawmakers and anti-poverty campaigners.

The Resolution Foundation, a think-tank which focuses on living standards, said only one in eight workers will see their tax bills fall over the next two years.

It also said absolute poverty was expected to rise by 1.3 million people next year, including half a million children, as inflation heads for around 9% later this year, outpacing pay and welfare benefits.

“Rishi Sunak has prioritised rebuilding his tax-cutting credentials over supporting the low-to-middle income households who will be hardest hit from the surging cost of living,” Resolution Foundation Chief Executive Torsten Bell said.

Britain’s budget watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, said Sunak undid only one-sixth of his previously announced tax rises aimed mainly at funding health and social care after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Newspapers, which have long cast Sunak as a future successor to Prime Minister Boris Johnson, criticised him for not doing enough to support people on the lowest incomes.

The Daily Express ran a headline: “The Forgotten Millions Say: What About Us?”

A survey published by polling firm Opinium after Sunak’s announcement – but conducted earlier this month – showed opposition Labour Party leader Keir Starmer and his would-be finance minister Rachel Reeves had overtaken Sunak and Johnson when people were asked who they trusted most to run the economy.

In media interviews on Thursday, Sunak defended his plans, offering scenarios showing how many workers stood to be better off. He also said he could not completely offset the jump in inflation which has been aggravated by the conflict in Ukraine.

But the Institute for Fiscal Studies, another think tank, said his decision last year to raise social security rates from April – which was only partially softened on Wednesday by a higher payments threshold – combined with a lower income tax rate made the tax system less equitable and less efficient.

IFS director Paul Johnson said this would widen the gap between taxes on earnings and those on pensions and unearned income.

“His choice to increase national insurance rates and reduce the basic rate of income tax looks, to me at least, indefensible from an economic point of view – though one can see the political attractions,” Johnson said at a news conference.

Richard Hughes, chair of the OBR whose forecasts underpin the budget, said Sunak remained on course to push the government’s tax take to the highest since the 1940s.

He also said the roughly 30 billion pounds of wiggle room that Sunak has kept for future spending or tax cuts could easily be wiped out if there were further rises in energy prices or higher-than-expected Bank of England interest rates.

(Additional reporting by Alistair Smout; Writing by William Schomberg; Editing by Hugh Lawson)