By Simon Lewis and Humeyra Pamuk

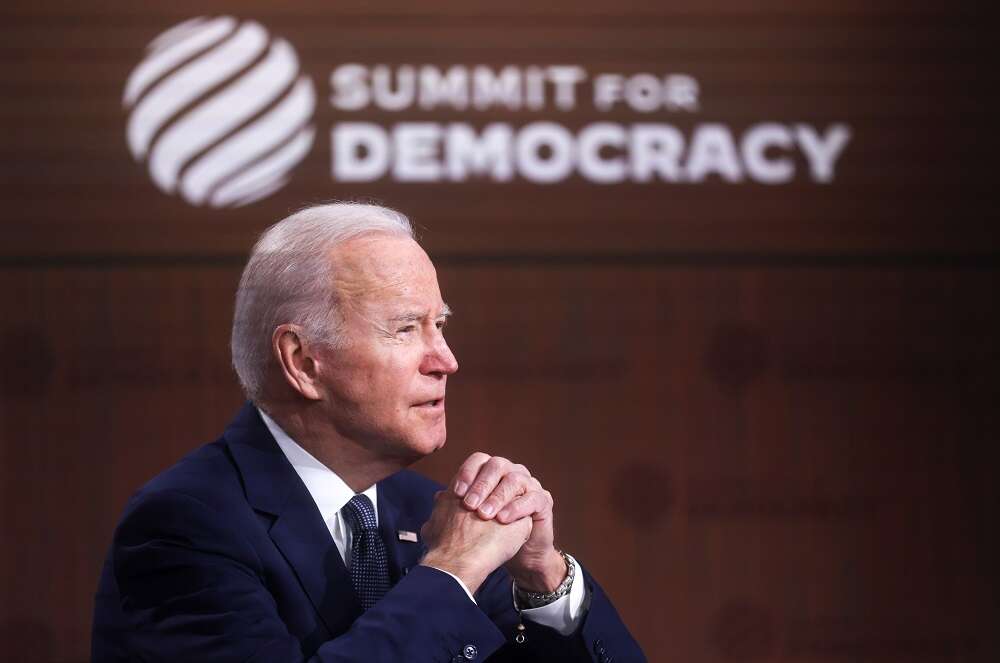

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. President Joe Biden gathered over 100 world leaders at a summit on Thursday and made a plea to bolster democracies around the world, calling safeguarding rights and freedoms in the face of rising authoritarianism the “defining challenge” of the current era.

In the opening speech for his virtual “Summit for Democracy,” a first-of-its-kind gathering intended to counter democratic backsliding worldwide, Biden said global freedoms were under threat from autocrats seeking to expand power, export influence and justify repression.

“We stand at an inflection point in our history, in my view. …Will we allow the backward slide of rights and democracy to continue unchecked? Or will we together have a vision…and courage to once more lead the march of human progress and human freedom forward?,” he said.

The conference is a test of Biden’s assertion, announced in his first foreign policy address in February, that he would return the United States to global leadership to face down authoritarian forces, after the country’s global standing took a beating under predecessor Donald Trump.

“Democracy doesn’t happen by accident. And we have to renew it with each generation,” he said. “In my view, this is the defining challenge of our time.”

Biden did not point fingers at China and Russia, authoritarian-led nations Washington has been at odds with over a host of issues, but their leaders were notably absent from the guest list.

The number of established democracies under threat is at a record high, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance said in November, noting coups in Myanmar, Afghanistan and Mali, and in backsliding in Hungary, Brazil and India, among others.

U.S. officials have promised a year of action will follow the two-day gathering of 111 world leaders, but preparations have been overshadowed by questions over some invitees’ democratic credentials.

The White House said it was working with Congress to provide $424.4 million toward a new initiative to bolster democracy around the world, including support to independent news media.

This week’s event coincides with questions about the strength of American democracy. The Democratic president is struggling to pass his agenda through a polarized Congress and after Republican Trump disputed the 2020 election result, leading to an assault on the U.S. Capitol by his supporters on Jan. 6.

Republicans are expanding control over election administration in multiple U.S. states, raising concerns the 2020 midterm elections will be corrupted.

The summit also included Taiwan, prompting anger from China, which considers the democratically governed island part of its territory.

A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson said the invitation of Taiwan showed the United States was only using democracy as “cover and a tool for it to advance its geopolitical objectives, oppress other countries, divide the world and serve its own interests.”

‘LIP SERVICE’

Washington has used the run-up to the summit to announce sanctions against officials in Iran, Syria and Uganda it accuses of oppressing their populations, and against people it accused of being tied to corruption and criminal gangs in Kosovo and Central America.

U.S. officials hope to win support during the meetings for global initiatives such as use of technology to enhance privacy or circumvent censorship and for countries to make specific public commitments to improve their democracies before an in-person summit planned for late 2022.

Some question whether the summit can force meaningful change, particularly by leaders who are accused by human rights groups of harboring authoritarian tendencies, like the Philippines, Poland and Brazil.

Annie Boyajian, director of advocacy at nonprofit Freedom House, said the event had the potential to push struggling democracies to do better and to spur coordination between democratic governments.

“But, a full assessment won’t be possible until we know what commitments there are and how they are implemented in the year ahead,” Boyajian said.

The State Department’s top official for civilian security, democracy and human rights, Uzra Zeya said civil society would help hold the countries, including the United States, accountable. Zeya declined to say whether Washington would disinvite leaders who do not fulfill their pledges.

Human Rights Watch’s Washington director Sarah Holewinski said making the invitation to the 2022 summit dependent on delivering on commitments was the only way to get nations to step up.

Otherwise, Holewinski said, some “will only pay lip service to human rights and make commitments they never intend to keep.”

“They shouldn’t get invited back,” she said.

(Reporting by Simon Lewis and Humeyra Pamuk; Additional reporting by Daphne Psaledakis and Nandite Bose; Editing by Mary Milliken, Heather Timmons and Alistair Bell)